Gábor Pap

Lessons learned in half a century

“Let us remember the people of old.” The story begins in 1977. At that time we organised a grand – and very impactful – exhibition in Debrecen, in the aula of Kossuth Lajos University, titled Roads from Folk Art. The considerations relating to the selection and arrangement were all but identical to those of the current show. Then the material went on to tour the country as a travelling exhibition. First to the capital, where it was hosted by the University of Technology, then by the University of Medicine, and ultimately to Szolnok, where it ended its journey in what was then known as the Komarov Hall. Some of the ‘big names’ featured in the current exhibition were already there, such as Géza Samu and Miklós Halmy; the comprehensive introduction and appraisal was written by István Kerékgyártó, which was published in the art journal Művészet [Art] issue 1 of 1978.

Later the same year, another exhibition with a similar motivation and aim behind it was held in Kecskemét, titled In the Spirit of Folk Art, which also attracted considerable attention. It might be worth quoting some of the ideas from the foreword of its catalogue since what can be learned from them is still relevant.

“Instead of a lengthy introduction, as a kind of warm-up, let’s run through some currently very popular notions.

Round 1: Let’s start with the assumption that folk art, like all human activities of a so-called ‘superstructure’ nature, is linked to a certain economic and social basis, and that once this basis is lost, folk art will also cease to exist. (Completely and for good – a jeering comment can already be heard from somewhere in the background, which, of course, is just the private opinion of the heckler, albeit without any evidence, but that is not something usually revealed.)

Round 2: Those who nevertheless wish to cultivate the heritage of folk art in our country today – because, against all expectations, such people do exist, and their number is apparently increasing every year – may face the following, needless to say, most unfounded accusations:

a) They wish to satisfy a non-existing need.

b) They indulge in a passing fad.

c) Rather than dealing with the more exciting problems of the present, they dwell on the past.

d) They are nationalists, or even worse.

e) They opt for simple ornamentation over a more substantial and autonomous visual communication.

f) Etc., etc. ...

To take any of the above statements (assumptions) seriously, it would have to be believed that;

1a) Folk art can be unconditionally and fully identified with the artistic activity (or an activity classifiable as such) of those historical ‘classes or strata of society’ that actually existed in one and only one social formation and which, when it disappeared, vanished without a trace.

2/a) There is currently no society-wide demand for a type of art that would attempt to outline and create a complete and organic world view, for which the folk art of any time and place (as long as it is worthy of the name) can offer a suitable model.

2/b) Folk art has no more to say to the society of today and tomorrow than any short-term fashion craze might.

2/c) Folk art has absolutely nothing to say – and by definition it cannot have anything to say – to the society of today or tomorrow.

2/d) Folk art can only offer lessons for one particular group of people (if at all - cf. points b) and c)), and only at the expense of all other peoples.

2/e) Finally, “folk art is primarily of an ornamental nature characterised by stylisation of a geometric spirit” – as a renowned researcher pointed out categorically in 1976, citing György Lukács. In other words, we should not expect more complex, sophisticated messages from it. […]

So in this way – but only in this way – all thwose who dare to find in folk art more than mere ornamentation or a very limited utilitarian value can still be easily classified as ‘romantics chasing rainbows with their heads in the clouds’… But – let us repeat – only in this way.”

So this is where we were in 1977. But... in the meantime, a new generation has grown up with a broader vision and better resistance. We have new ‘big names’ to learn. First and foremost, there is the school-founder Sándor Makoldi, but right next to him (and not after him) is the exceptional Peter Földi, whose pupils now also have to be reckoned with. Then, still in Debrecen, Géza Sulyok, István Horváth and Antónia Szabó, László Buka, or a bit further away, the teachers of the Nádudvar Vocational School of Folk Crafts, with Mihály Vetró leading the way. By now, even their students are also demonstrating their talents. Moving on to Kecskemét, the Vidáks, István and his partner, Mari Nagy... Parents and children. And again and again the students. The list is almost endless. So is it possible to speak in this language? Is there anyone who will listen?

There are still plenty of open questions. Including some not insignificant ones. But this is not so much a problem for the artists as it is for their – nowadays evil and step- – mother, the social environment around them, or, to put it more precisely, the ‘consumer base’. Why beat around the bush? The society in which they were destined to produce art has quite simply forgotten to think in quality terms. It only knows numbers. How many people registered for your exhibition? How many times have you appeared in the media? How many people ‘liked’ your appearance? How many pictures can you sell in a unit of time? Your monthly income? Your blood pressure? We need exact figures! Is this the kind of environment in which you want to be ‘popular’?

We must be aware that the current ‘trend’ is to assign to every fact, to every possibility, a number of a comparable scale, and that this number – whatever it takes – must increase day by day. This is the measure of success, and success is the indisputable stake in everything we do. But human beings, as creatures made up of three components, soul, spirit and body (trichotomous in technical terms), are sui generis incapable of satisfying such a universal need. We are not even taken into account in the long run by the powers that plan and control our destiny from the background. Let’s just call a spade a spade: we are being turned into bio-robots so that we can be scrapped without a second thought when our work is done. Because robots powered by artificial intelligence already do everything better, more accurately and more reliably. This is not some irrational belief, but a cold empirical fact. In such a ‘brave new world’, where can an artistic practice that describes itself as ‘organic’ and ‘universal’ find a place? And will it, or can it, find one at all?

Well... it can and it does. In fact, the need for it is greater than ever. This is not our first warning, we already made one half a century ago: if we want to survive this Orwellian age as human beings we have to have this intellectual reserve up our sleeve. Back then, there were people who believed us. They lived to see the present age enriched in their humanity - quietly but noticeably. (Both adjectives, ‘quietly’ and ‘noticeably’, are equally relevant.)

In the course of our lives, we constantly and regularly alternate between two necessarily complementary phases of work. One is called – in a term borrowed from the Middle Ages – vita activa, the active way of life, the other vita contemplativa, meaning contemplative or maturing. These terms can be applied not only to individuals but also to nations. Which of the two applies best to Hungarians today? I would be delighted if we could agree: we collect the vital spiritual assets in a state of contemplation, of inward maturation. Because we all know that we are in the end game, and that only these can provide guaranteed effectiveness for survival in a worthy form. Equipped with this knowledge, we enter 2023, and the realm of wonders that is waiting for us in the Kunsthalle Budapest.

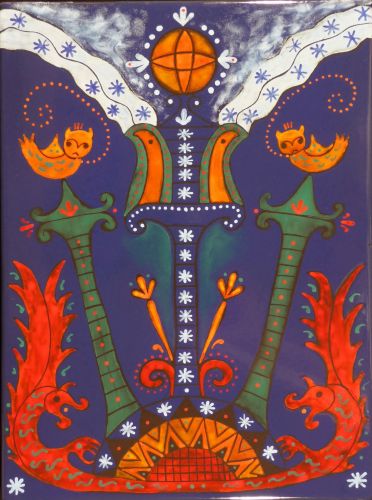

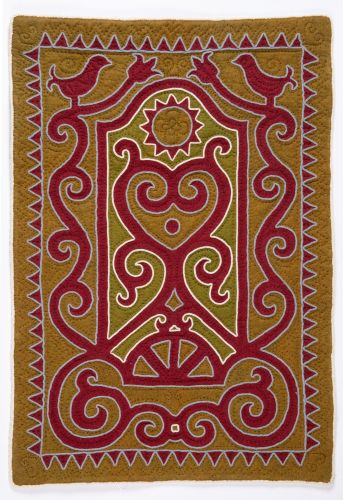

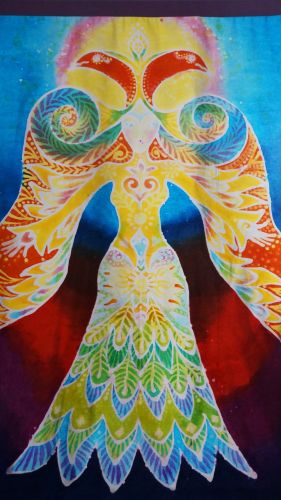

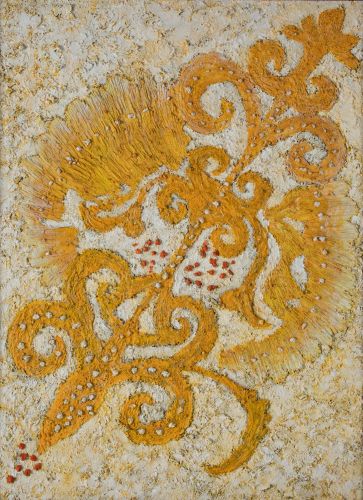

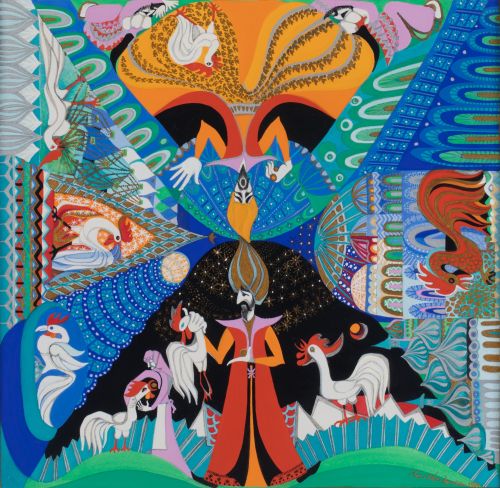

We could just as well close this brief introduction here but then it would end on a somewhat lofty note. Why not end with a lesson in more prosaic terms? At the time of writing, we have not yet had the opportunity to take a good look at the entire collection of works in their original form nor in sufficient detail. However, on the basis of the list of titles, and being familiar with many of the works to be exhibited from the past, we were able to observe that the most powerful works, the ones with the most prospective messages, usually did not find their “authentic” source in the domain of ethnography, nor in some “skill”, nor in its “decorative” material. (No more quotation marks, I promise.) Where then? In the realm of intellectual ethnography, in the motif range of textual

folk art. In a folk tale (Sándor Makoldi: Son of the White Mare) or in a ballad (Péter Földi: Owl Woman). As if this phenomenon wanted to remind us, its observers, that what can be formulated about the whole wide world in images, and is also worth the effort, has already been formulated by Zsiga Király, József Hodó, and Józsi Jóna, and that there is nothing else about them, or at least if there were it would be very difficult, or even unnecessary, to further elaborate upon. On the other hand, our folk poetry basically uses images to formulate its ideas, and it is all the more possible and even worthwhile to elaborate these visual suggestions on canvas, on paper, or perhaps in small sculptures, with authenticating points of emphasis, to further formulate them into messages with new lessons for tomorrow. And lo and behold...

And as for the incessant accusations that criticize the reverie in the past, if someone were to attack us saying that we should stop struggling because – so they say – the past cannot be brought back anyway, let us respond with László Hintalan’s parable, which by now has become a classic in terms of importance and rank:

If a child is lost and we bring him or her home, are we bringing back the past?

If a river is polluted and we clean it, are we bringing back the past?

If we have a quarrel but we eventually make up, are we bringing back the past?

With all these lessons learned, we can now send the respected visitors “indulging in the past” on their tour of the exhibition with a calm mind.