Gabriella Igyártó

SoulShapes – Thirty-three

“There was a time when even the most excellent scholars could not see anything else in human culture but the reflection of the milieu, the world that surrounded them, and they were seeking it everywhere. People today are interested in others, with whom they can meet in the various forms of culture: in language, the arts and customs. We want to get to know the soul of Hungarians even when we admire their artistic creations.”

(Gábor Lükő: Shapes of the Hungarian Soul)

The name of the exhibition hall is both a reference to the number of displayed objects and Christ’s age at his death, signifying the turning point when people can meet the divine living inside of them. And creation is the manifestation of this divine. By creating something people become part of creation itself through bringing new things into the world. It is these new things that appear before us in the exhibition space.

When denoting an age, the number 33 refers to a young adult. In Room Thirty-three visitors can see 33 works by 33 young artists inspired by folk art. If art is the act of “an individual seeking his or her place in the world” and if “folk art belongs to communities”, then, as Mihály Vetró writes in the introduction of the exhibition catalogue, the objects exhibited in Room Thirty-three are manifestations of young adults seeking their path, looking for connections between old and new, between past and present. The diverse ways in which these works evoke the past clearly exemplifies the wide spectrum in which the past can form part of our present lives.

Today’s young adults did not personally experience the living conditions and necessities of life that Bertalan Andrásfalvy mentions in this catalogue. Thus, their works could not have possibly been conceived from such inspiration – at best they were able to draw on existing customs, stories or studies evoking the old times, which, however, are all interpretations conveyed by people of today and as such they underwent a certain transformation. It is obviously important to remember the past. It is important to know the customs of our communities, our nation’s history and our family’s stories as they constitute our origins: our humanity is rooted in them. At the same time, from the perspective of our survival and lives it is equally important to be able to adapt to the increasingly rapid changes of the contemporary world. If only presented in glass cases, sculptures and books, our remembrance of the past will fade away and eventually vanish. If we cannot ‘keep it functional’, the world will ‘rush past it’. Compared with the times of our ancestors, today beauty is seen differently, different sounds are heard as pleasant, propriety in clothing means something else and our hands find different things usable. Of course we can nostalgically reach back for an object, a family memento or a household item but if they no longer have a useful function, they will sooner or later end up in the attic.

The artists of Room Thirty-three all want to create things for the present. Their objects bear their approach to the contemporary world. Some of their works have a stronger evocation of the past and are closer to the source, while others are more dominated by functionality. There are artists who come from arti san families and mastered their knowledge at home, but others simply heard a calling and arrived at folk art along a winding path without any previous history, merely urged on by a desire to create something. All the artists, however, share a love of nature, a reverence for ancient forms and materials and they are touched by the Soul, which, in this part of the world, is very Hungarian and carries our entire collective history. They all agree that this is only the starting point, from where they take a leap, soar freely and reach the present, where, fulfilling themselves, they can become the basis for future generations, who will become creative artists in a world we cannot yet imagine.

The makers of the displayed objects come from all corners of the country, from its furthest part to its closest, since some are from Budapest, which confirms the idea that once someone has the desire to create something and they are touched by the ancient spirit exuding from folk art, a milieu for artistic creation can be found even amidst the bustle of a capital’s concrete jungle.

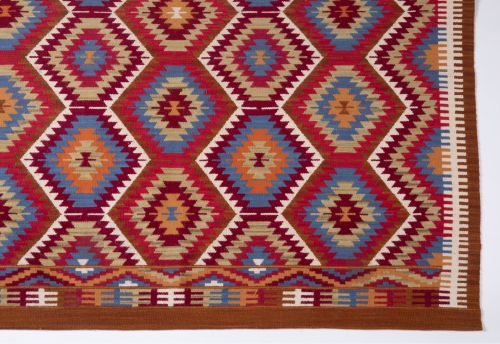

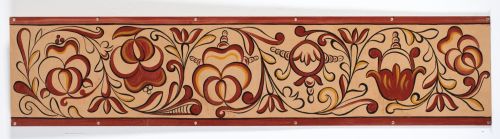

Visitors to the exhibition can become familiar with 13 crafts and 33 craftsmen, whose talent has been highly valued by professional juries. Several of the exhibitors have won the Junior Prima Award and the Young Master of Folk Art title. The 13 crafts are: weaving, felt-making, leather working, instrument-making, attire-making, embroidery, wood-carving, furniture-painting, egg-decorating, whip-making, button-making, pottery and bell-casting. When laymen think of object-making folk art, what comes to their mind is embroidered blouses and tablecloths or at most masterly carved wooden or painted chests. At our exhibition, however, that folk art imbues every facet of life. What was once a decorated object of everyday use reflecting its maker’s dexterity has ennobled into a much-treasured work of art. The displayed objects demonstrate their makers’ professional knowledge, manual skills, imagination and creativity but on a par with these are aesthetic design, beauty and artistic value.

This is all a process, with some of it already being history. It was exactly fifty years ago that Sándor Csoóri wrote in his notes in connection with the foundation of the Young Folk Art Studio: “Young folk artists coming on the scene in nineteen seventy-three? Perhaps the re-emergence of natural talents? Of artificial peasants rubbed with rancid bacon? Of the Ufo-youths of the nation? Or of bankrupt painters, sculptors, ceramic artists and goldsmiths looking for an emergency exit through the cellar door of folk art, which has become trendy again? These questions – let me quickly add – are not mine but those asked by suspicious people, the storekeepers of prejudice, who, whenever they hear about affairs linked to folk culture, cannot help but hear the echo of bygone days. Something that is obsolete, under the ground, and only for dead ears, not for us here.

The young folk artists who founded the Studio, including a wood carver who is »a natural talent«, a ceramic artist with a nationwide reputation and a modern architect alike, seek to end this very inequality between cultures. The young people coming together in this intellectual workshop have a similar aspiration. They primarily seek to renew folk art not within its own confines but in various other contexts. In other words, even though they regard folk art as a journey and a primal source, they definitely do not see it as the final destination. Even if some of them will copy a plate, a jug or a bottle, or the sleeve of a blouse embroidered in red or black, they will do so not to express their sympathy for the customs and culture of a people, or to decorate the walls of an exhibition hall for a few weeks, but rather to make this most elemental way of using folk art accepted in the new synthesis. Perhaps I need not say that even with its powerful objectives the Studio does not aspire to have monopoly. Rather autonomy, enabling it to be an equal rival to the narrow-minded, stale »folk art« production of goods that overflows in its sentimentality and gaudiness, misleading not only tourists but Hungarians too, and promoting, for some fatal misunderstanding, the commercialised Hungarian soul.” 01

The Young Folk Artists’ Studio, celebrating its fiftieth anniversary this year, and the members of the Nomad Generation have an inevitable role in the rediscovery of our folk art and in the renewal of Hungarian crafts. Also crucially important is the dedicated work that has been continually carried out in the Nádudvar School of Crafts, now 30 years old, and the Alliance of Folk Art Associations, 40 years old this year. The re-training of traditional crafts that is done in their programme is only one of the stages of a process; the next one is to reach the master level but the most important thing is what also appears in each element of our exhibition, and especially in Room Thirty-three to make tradition usable. To make dancing and singing a source of joy, an aesthetic dress wearable, a beautiful decorated bag practical, a skilfully carved knife fit the hand and richly embroidered pillowcase a lovable ornament of a modern home. This part of the exhibition, therefore, seeks to showcase usable folk art.

In addition to their desire to create, the majority of artists of Room Thirty-three take a part in passing on their knowledge despite their young age. They are aware that continuity cannot be broken; moreover, continuity is the main thing. The exhibit objects only draw attention to beauty, function, past rekindled in the present, and they can become sources of inspiration. It is thus no wonder that this room is the venue for events organised for children, in which creative work with materials, i.e. handicrafts go hand in hand with games, music and dancing, all natural forms of being for children (and for mankind in general). As children learn to stand, they immediately start dancing. They feel the music and its rhythm. The moment they know how to manipulate objects, they start building, rearranging and making something new from something old. First they do this alone, exploratively, and then in a community, with their peers. Things that surrounded them in their youngest years will be the dearest to them all their lives. They will be the foundation in their lives and an indelible attachment to the local manifestations of soul-shapes. Children (and parents) who will participate in the events during this exhibition will get a taste of what value, aesthetic quality and beauty is, to which they can later adapt their reference system.

The mission of the Alliance of Folk Art Associations is exactly this: providing foundation and attachment, passing, carrying on and reinventing things. The message of our greatest festival, the Festival of Folk Arts, is reflected the most by Room 33 of the current exhibition, underlining that while the old, the masters, are the keepers, the young are the ones carrying things on and they should be allowed to use their knowledge for their art in the way through which they can address the contemporary world. Only then can we ensure continuity and survival, and only then is remembrance meaningful.

Folk art is the manifestation of the Soul: it draws sustenance from the soil where we were born and it mediates us into the world in which we live.

Footnotes

01 Sándor Csoóri: Érték és időszerűség. Jegyzet a Fiatalok Népművészeti Stúdiójáról [Value and Timeliness. Notes on the Young Folk Artists’ Studio]. Tiszatáj, 1973/8.